The Big Mo' - Momentum In Sports

/We know it as the "Big Mo", the "Hot Hand", and being "In The Zone" while the psychologists call it Psychological Momentum. But, does it really exist? Is it just a temporary shift in confidence and mood or does it actually change the outcome of a game or a season? As expected, there are lots of opinions available.

The Oxford Dictionary of Sports Science defines psychological momentum as, "the positive or negative change in cognition, affect, physiology, and behavior caused by an event or series of events that affects either the perceptions of the competitors or, perhaps, the quality of performance and the outcome of the competition. Positive momentum is associated with periods of competition, such as a winning streak, in which everything seems to ‘go right’ for the competitors. In contrast, negative momentum is associated with periods, such as a losing streak, when everything seems to ‘go wrong’."

The interesting phrase in this definition is that Psychological Momentum (PM) "affects either the perceptions of the competitors or, perhaps, the quality of performance and the outcome of the competition." Most of the analyses on PM focus on the quantitative side to try to prove or disprove PM's affect on individual stats or team wins and losses.

Regarding PM in baseball, a Wall St. Journal article looked at last year's MLB playoffs, only to conclude there was no affect on postseason play coming from team momentum at the end of the regular season. More recently, Another Cubs Blog also looked at momentum into this year's playoffs including opinion from baseball stats guru, Bill James, another PM buster. For basketball, Thomas Gilovich's 1985 research into streaky, "hot hand" NBA shooting is the foundation for most of today's arguments against the existence of PM, or at least its affect on outcomes.

This view that if we can't see it in the numbers, more than would be expected, then PM does not exist may not capture the whole picture. Lee Crust and Mark Nesti have recommended that researchers look at psychological momentum more from the qualitative side. Maybe there are more subjective measures of athlete or team confidence that contribute to success that don't show up in individual stats or account for teams wins and losses.

As Jeff Greenwald put it in his article, Riding the Wave of Momentum, "The reason momentum is so powerful is because of the heightened sense of confidence it gives us -- the most important aspect of peak performance. There is a term in sport psychology known as self-efficacy, which is simply a player's belief in his/her ability to perform a specific task or shot. Typically, a player’s success depends on this efficacy. During a momentum shift, self-efficacy is very high and players have immediate proof their ability matches the challenge. As stated earlier, they then experience subsequent increases in energy and motivation, and gain a feeling of control. In addition, during a positive momentum shift, a player’s self-image also changes. He/she feels invincible and this takes the "performer self" to a higher level."

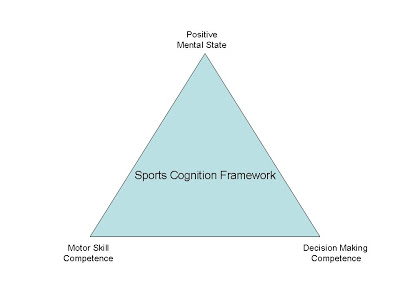

There would seem to be three distinct areas of focus for PM; an individual's performance within a game, a team's performance within a game and a team's performance across a series of games. So, what are the relationships between these three scenarios? Does one player's scoring streak or key play lift the team's PM, or does a close, hard-fought team win rally the players' morale and confidence for the next game?

Seeing the need for a conceptual framework to cover all of these bases, Jim Taylor and Andrew Demick created their Multidimensional Model of Momentum in Sports, which is still the most widely cited model for PM. Their definition of PM, "a positive or negative change in cognition, affect, physiology, and behavior caused by an event or series of events that will result in a commensurate shift in performance and competitive outcome", leads to the six key elements to what they call the "momentum chain".

First, momentum shifts begin with a "precipitating event", like an interception or fumble recovery in football or a dramatic 3-point shot in basketball. The effect that this event has on each athlete varies depending on their own perception of the game situation, their self-confidence and level of self-efficacy to control the situation.

Second, this event leads to "changes in cognition, physiology, and affect." Again, depending on the athlete, his or her base confidence will determine how strongly they react to the events, to the point of having physiological changes like tightness and panic in negative situations or a feeling of renewed energy after positive events.

Third, a "change in behavior" would come from all of these internal perceptions. Coaches and fans would be able to see real changes in the style of play from the players as they react to the positive or negative momentum chain.

Fourth, the next logical step after behavior changes is to notice a "change in performance." Taylor and Demick note that momentum is the exception not the norm during a game. Without the precipitating event, there should not be noticeable momentum shifts.

Fifth, for sports with head to head competition, momentum is a two-way street and needs a "contiguous and opposing change for the opponent." So, if after a goal, the attacking team celebrates some increased PM, but the defending team does not experience an equal negative PM, then the immediate flow of the game should remain the same. Its only when the balance of momentum shifts from one team to the other. Levels of experience in athletes has been shown to mitigate the effects of momentum, as veteran players can handle the ups and downs of a game better than novices.

Finally, at the end of the chain, if momentum makes it that far, there should be an immediate outcome change. When the pressure of a precipitating event occurs against a team, the players may begin to get out of their normal, confident flow and start to overanalyze their own performance and skills. We saw this in Dr. Sian Beilock's research in our article, Putt With Your Brain - Part 2. As an athlete's skills improve they don't need to consciously focus on them during a game. But pressure brought on by a negative event can take them out of this "automatic" mode as they start to focus on their mechanics to fix or reverse the problem.

As Patrick Cohn, a sport psychologist, pointed out in a recent USA Today article on momentum, "You stop playing the game you played to be in that position. And the moment you switch to trying not to screw up, you go from a very offensive mind-set to a very defensive mind-set. If you're focusing too much on the outcome, it's difficult to play freely. And now they're worried more about the consequences and what's going to happen than what they need to do right now."

There is no doubt that we will continue to hear references to momentum swings during games. When you do, you can conduct your own mini experiment and watch the reactions of the players and the teams over the next section of the game to see if that "precipitating event" actually leads to a game-changing moment.

Jim Taylor, Andrew Demick (1994). A multidimensional model of momentum in sports Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, 6 (1), 51-70 DOI: 10.1080/10413209408406465