The following is an excerpt from the introduction to The Playmaker’s Decisions, now available at http://geni.us/theplaymakersdecisions

© copyright 2020 Daniel R. Peterson and Leonard Zaichkowsky

As the confetti floated down from the top of Mercedes-Benz Stadium in Atlanta, Nick Saban stopped Tom Rinaldi in his tracks. The veteran ESPN reporter had his opening question queued until the Alabama football head coach patted his chest with a wry grin to declare, “I’m asking the questions.” Rinaldi yielded the microphone, to which Saban asked an obvious, rhetorical question, “Was that a good game or what?” Saban and his Crimson Tide had just walked off with the 2018 College Football Playoff national championship in an overtime thriller against the Georgia Bulldogs. It was Saban’s sixth national championship tying his idol, former Alabama coach Paul “Bear” Bryant, for most all-time in the modern era of the sport.

At the end of the last decade, pundits hailed that game as one of the most exciting and competitive of the last ten years, not only in college football but across all sports. Georgia entered the game as four point underdogs to the perennial powerhouse Alabama, even though Clemson upset Saban’s squad a year earlier in the title game. That loss motivated the Crimson Tide from the final whistle to the first day of Spring practice to the opening week of the 2017-18 season where Saban told the SEC media, “Hopefully, we don’t waste a failure.” His coaching method, popularly known as The Process, takes its origin from his days as a young defensive coordinator with the Cleveland Browns. There he worked for another aspiring coach, Bill Belichick, who was instilling his own succinct but motivational mantra to “do your job.” Today, almost thirty years later, they are the most successful head coaches in the history of college and professional football, respectively, with six championship trophies each.

So, when the Bulldogs went into the locker room at halftime with a 13 point lead, having held Alabama to just 21 passing yards, Nick Saban knew he must make a change. Not just a tweak to his playbook, not just an encouraging rant to his players, but a fundamental shift in his game plan. He called together two of his quarterbacks, starter Jalen Hurts and backup Tua Tagovailoa, to tell them that Tua would start the second half. At that point in his college career, the freshman Tagovailoa had yet to start a game, so inserting him into the national championship at halftime, down by two touchdowns, seemed illogical to fans and commentators. But they cautiously gave Saban, already a legend, the benefit of the doubt.

The decision became one for the ages, as Tua resuscitated Alabama with 166 yards of second half passing and three touchdowns including the game winning 41-yard throw to DeVonta Smith on the second play of their overtime possession. Despite his usual stoic, “take what the opponent gives you” demeanor, Saban is the same coach who called an onside kick with the score tied in the national title game two years earlier against Clemson. That successful conversion and drive ended with a touchdown leading to his fifth trophy.

And while these extraordinary decisions get the headlines, Saban would be the first to remind us of the hundreds of micro-decisions made by his players, the opponents and the officials throughout any four quarters. Even in that 2018 game, fast, in-the-moment decisions, both good and bad, contributed to the outcome. Decisions to pass to a certain receiver, to use a different technique against a lineman, to overreact and retaliate against an opponent, or to throw a momentum shifting penalty flag change the moment, which, taken together, change the outcome. Nothing happens in a game without a decision, whether it be a conscious choice or a subconscious reaction to an ever-changing set of stimuli. Post game analyses lament the mental mistakes and the missed opportunities. Just as often, the clutch plays and the appearance of genius insight garner praise. However, consistent, superior decision-making is part of “your job” as an athlete, coach or official.

Inside the play-by-play minutiae of sport, each choice stands on its own as a drop of water that still contributes to the full glass. And that is all one person can focus on at any one time, just his or her next action in the next play. Blocking everything else out is the only way to manage the noise from a thousand variables that only confuse the brain. Those tiny, consecutive steps create the process that Saban preaches. Think of this compartmentalization as being present in the moment. “Don’t think about winning the SEC Championship,” said Saban. “Don’t think about the national championship. Think about what you needed to do in this drill, on this play, in this moment. That’s the process: Let’s think about what we can do today, the task at hand.”

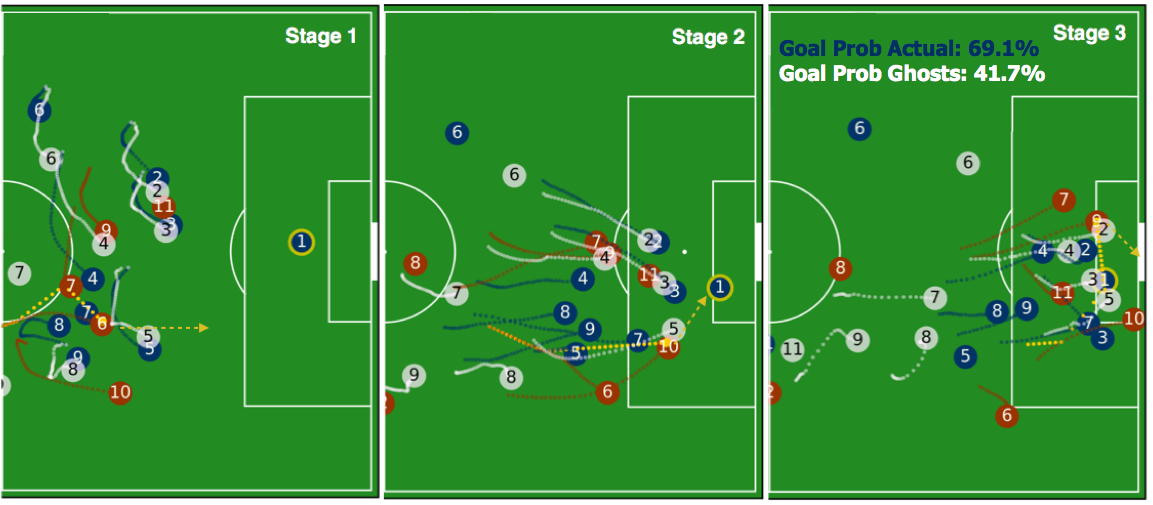

In our 2018 book, "The Playmaker’s Advantage", we explored the mind of a player like Tagovailoa - one that can take over a game with superior “athlete cognition.” Actually, we coined that term trying to describe the mental process that repeated itself hundreds of times a game. Athlete cognition consists of three interwoven sub-processes; Search-Decide-Execute or See-Think-Do. The first and last parts build on decades of research on perception and skill acquisition, respectively. But the mushy middle is still a mystery. What goes on inside the “black box” of decision-making hides from view. We can prepare an athlete with pre-game information and tactics, then recap their decision quality post-game. But getting under the hood to work on the engine of decisions is more difficult.

Buying a new car or evaluating a loan application or planning a vacation are processes that combine the input of data, a decision algorithm, and the output of a plan. And while the consequences of those types of decisions may be significant, there is a unique approach to arriving at the best option. In those scenarios, there is time to collect more information, as well as hours if not days to process, ponder and predict possible outcomes. However, in a game, competition, or any high pressure environment, the crucible of tension dictates a faster process.

In sports, just as in any action-oriented activity, vision and perception provide the input while our well-trained motor skills deliver the output. Go left or go right? Pass or shoot? Foul or don’t foul? Given the same sensory details from a chaotic game environment, how and why do players make different choices? In post-game reviews, they regret the errors, sometimes surprised that they were capable of such a blunder. Just as confusing is the unconscious flow that can place them squarely in the zone where decisions come instantly and effortlessly, leading to an outstanding performance.

And that’s why we continued the search, this time drilling down into the muddy middle. After reading our first book, coaches and players asked us to pull back the curtain to see who is controlling the levers, specifically on what drives decisions and how to train this skill.

The Athlete Decision Model

As with the Athlete Cognition process, Dr. Len and I knew we needed to visualize a new framework to talk about the decision-making process. We have cleverly named this the Athlete Decision Model or ADM. We tried hard to brainstorm a catchy acronym but opted for simplicity. Given the input of their surroundings through sight, sound, and a mental radar of those around them, players may perceive varying degrees of reality. So, the raw material that they have to work with to make their next decision is not equal. In the same way, the only tangible outcome of a decision is the action taken by the player. We know that a running back decided to cut left then right because we see it live. The skill requires and follows the decision.

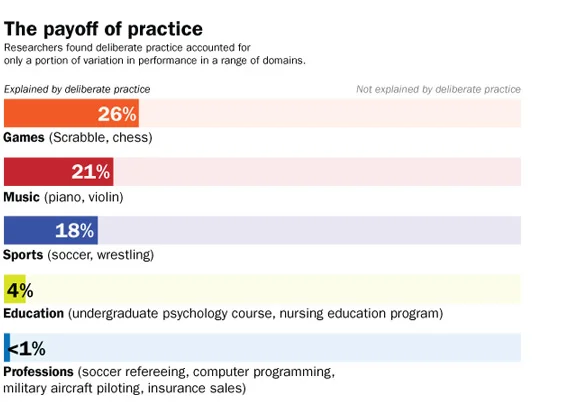

But how well he executes that move, the quickness and the angle of direction change, is a motor skill that combines some genetic gifts but mostly with what we call hours of deliberate, intentional practice. Plenty of running backs may choose the same elusive maneuver but may not have the same jaw-dropping control of gravity that a playmaker possesses. These are abilities on both the front end and back end of a decision that vary from player to player, and determine which decisions are possible and their final execution.

Get your copy of The Playmaker’s Decisions at your favorite online bookstore: http://geni.us/theplaymakersdecisions