Athletes In The Zone Feel The Flow

/ |

| Robyn Beck/Getty Images |

After a great performance, many athletes have described a feeling of being “in the zone.” In this state, they feel invincible, as if the game slowed down, the crowd noise fell silent and they achieved an incredible focus on their mission. What is this Superman-like state and how can players enter it when they most need it?

Like the feeling of being moved down a river by the current, this positive groove has been described as a "flow." In fact, Mihaly Csíkszentmihályi, psychology professor at Claremont Graduate University in California, coined the term in his 1990 book, “Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience” (Harper Row, 1990).

From his years of research, Csíkszentmihályi developed an entire theory around the concept and applied it not only to sports, but also to work life, education, music and spirituality.

Csíkszentmihályi identified nine components of the state of flow. The more of these you can achieve, the stronger your feeling of total control will be.

1. Challenge-skills balance is achieved when you have confidence that your skills can meet the challenge in front of you.

2. Action-awareness merging is the state of being completely absorbed in an activity, with tunnel vision that shuts out everything else.

3. Clear goals come into focus when you know exactly what is required of you and what you want to accomplish.

4. Unambiguous feedback is constant, real-time feedback that allows you to adjust your tactics. For example, fans and coaches will let you know how you're doing.

5. Concentration on the task at hand, with laser-beam focus, is essential.

6. Sense of control is heightened when you feel that your actions can affect the outcome of the game.

7. Loss of self-consciousness occurs when you are not constantly self-aware of your success.

8. Transformation of time takes place when you lose track of time due to your total focus on the moment.

9. Autotelic experience is achieved when you feel internally driven to succeed even without outside rewards. You do something because you love to do it.

Flow doesn't only happen to athletes. In any activity, when you're completely focused, incredibly productive and have lost track of time, you may be in the flow. You may not be trying to win the U.S. Open, but you can still say you are "in the zone."

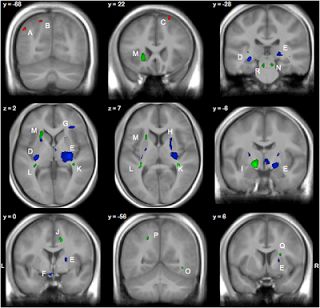

See also: Tiger's Brain Is Bigger Than Ours and Tiger, LeBron, Beckham - Neuromarketing In Action