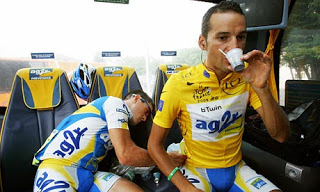

More Proof That Caffeine Boosts Athletic Performance

/

UK scientists show for the first time that high doses of caffeine directly increase muscle power and endurance during relatively low-intensity activities.

New research shows increased muscle performance in sub-maximal activities, which in humans can range from everyday activities to running a marathon. With no current regulations in place, the scientists from Coventry University believe their findings may have implications for the use of caffeine in sport to improve performance.

The scientists present their work at the Society for Experimental Biology Annual Meeting in Prague.

"A very high dosage of caffeine, most likely achieved via tablets, powder or a concentrated liquid, is feasible and might prove attractive to a number of athletes wishing to improve their athletic performance," explains lead researcher, Dr Rob James.

"A small increase in performance via caffeine could mean the difference between a gold medal in the Olympics and an also-ran," he added.

Caffeine is not currently listed by the World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA) as a banned substance at any concentration in blood or urine samples. Before 2004 WADA did set a specific level over which athletes could be banned, but this restriction was removed. Muscle activity is divided into maximal, where the muscles are pushed to full capacity such as in sprinting or weight lifting, and sub-maximal, which covers all other activities.

A member of the team, Jason Tallis, tested the effect of caffeine on both the power output and endurance of soleus muscles (lower leg muscle) in mice, under both maximal and sub-maximal activities.

He found that a caffeine dosage of 70 µM enhanced power output by ~6% during both types of activity. This effect in humans is likely to be very similar, according to the researchers.

He found that a caffeine dosage of 70 µM enhanced power output by ~6% during both types of activity. This effect in humans is likely to be very similar, according to the researchers.

"70 μM caffeine concentration is the absolute maximum that can normally achieved in the blood plasma of a human, however concentrations of 20-50 μM are not unusual in people with high caffeine intakes," explains Dr James.

Resultant caffeine in blood plasma (70μM maximum) may act at receptors on skeletal muscle causing enhanced force production. Scientists already know that ingestion of caffeine can increase athletic performance by stimulating the central nervous system. Additionally, 70μM caffeine treatment increased endurance during sub-maximal activity, but significantly reduced endurance during maximal activity.

Source: Society for Experimental Biology

See also: Starbucks' Secret Sports Supplement and How Should Cheating Be Defined In Sports?

New research shows increased muscle performance in sub-maximal activities, which in humans can range from everyday activities to running a marathon. With no current regulations in place, the scientists from Coventry University believe their findings may have implications for the use of caffeine in sport to improve performance.

The scientists present their work at the Society for Experimental Biology Annual Meeting in Prague.

"A very high dosage of caffeine, most likely achieved via tablets, powder or a concentrated liquid, is feasible and might prove attractive to a number of athletes wishing to improve their athletic performance," explains lead researcher, Dr Rob James.

"A small increase in performance via caffeine could mean the difference between a gold medal in the Olympics and an also-ran," he added.

Caffeine is not currently listed by the World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA) as a banned substance at any concentration in blood or urine samples. Before 2004 WADA did set a specific level over which athletes could be banned, but this restriction was removed. Muscle activity is divided into maximal, where the muscles are pushed to full capacity such as in sprinting or weight lifting, and sub-maximal, which covers all other activities.

A member of the team, Jason Tallis, tested the effect of caffeine on both the power output and endurance of soleus muscles (lower leg muscle) in mice, under both maximal and sub-maximal activities.

He found that a caffeine dosage of 70 µM enhanced power output by ~6% during both types of activity. This effect in humans is likely to be very similar, according to the researchers.

He found that a caffeine dosage of 70 µM enhanced power output by ~6% during both types of activity. This effect in humans is likely to be very similar, according to the researchers."70 μM caffeine concentration is the absolute maximum that can normally achieved in the blood plasma of a human, however concentrations of 20-50 μM are not unusual in people with high caffeine intakes," explains Dr James.

Resultant caffeine in blood plasma (70μM maximum) may act at receptors on skeletal muscle causing enhanced force production. Scientists already know that ingestion of caffeine can increase athletic performance by stimulating the central nervous system. Additionally, 70μM caffeine treatment increased endurance during sub-maximal activity, but significantly reduced endurance during maximal activity.

Source: Society for Experimental Biology

See also: Starbucks' Secret Sports Supplement and How Should Cheating Be Defined In Sports?