Preventing Burnout In Young Athletes

/

For many elite team coaches, the greater challenge in developing top young athletes is not improving the ones on your team, but rather finding the talented kids that got away from the sport. Keeping the next Lionel Messi or Michael Phelps involved and motivated from age 7 to 17 is becoming more difficult. While over 35 million kids between 4 and 14 play organized sports in the U.S., over 70% will drop out by age 13. According to new research, that drastically reduced talent pool may be caused by the athlete’s own psychological profile and how a coach manages it.

According to a 2004 study by Michigan State’s Institute for the Study of Youth Sport, here are the top ten reasons why boys and girls quit organized sports:

Boys

- I was no longer interested.

- It was no longer fun.

- The sport took too much time

- The coach played favourites.

- The coach was a poor teacher.

- I was tired of playing.

- There was too much emphasis on winning.

- I wanted to participate in other non-sport activity.

- I needed more time to study.

- There was too much pressure.

Girls

- I was no longer interested.

- It was no longer fun.

- I needed more time to study.

- There was too much pressure

- The coach was a poor teacher.

- I wanted to participate in other non-sport activities.

- The sport took too much time.

- The coach played favourites.

- I was tired of playing.

- Games and practices were scheduled when I could not attend.

Comparing the lists, when a young athlete loses interest and does not have fun, (partly because the coach applied too much pressure or they were a poor teacher), it may be due to their internal mindset based on an educational psychology concept known as the Achievement Goal Theory (AGT).

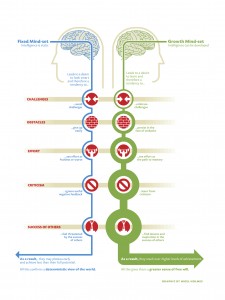

Psychologists Carol Dweck and Thomas Nicholls, while they worked together at the University of Michigan, both studied students who failed to learn and their research resulted in parallel tracks, just with different terminology. For Dweck, she defined two styles of learning motivation as Mastery and Performance. Take for example, a young soccer player that spends hours in the backyard learning to juggle a ball. For a player with a Performance mindset, he is practicing because of a desire to be the best juggler on the team or maybe because he is embarrassed by his lack of skill compared to his teammates.

On the opposite end, a player with a Mastery mindset is motivated to learn simply by the challenge of the skill without any competitive instincts. Nicholls uses the terms Task to compare with Dweck's Mastery and substitutes Ego instead of Performance. Both Dweck and Nicholls agree that the player’s perceived ability and competence also affects their motivation to keep trying to learn the new skill. Here’s a great video overview of the concepts by Professor Jonathan Hilpert of Georgia Southern University.

On the opposite end, a player with a Mastery mindset is motivated to learn simply by the challenge of the skill without any competitive instincts. Nicholls uses the terms Task to compare with Dweck's Mastery and substitutes Ego instead of Performance. Both Dweck and Nicholls agree that the player’s perceived ability and competence also affects their motivation to keep trying to learn the new skill. Here’s a great video overview of the concepts by Professor Jonathan Hilpert of Georgia Southern University.

In fact, in a study this year of 167 junior club soccer players in England, Andrew Hill, sports scientist at the University of Leeds, found that a quarter of the boys experienced symptoms of burnout.

"What we see among the athletes showing symptoms of burnout is emotional and physical exhaustion, a sense that they are not achieving and a sense of devaluation of the sport. Even though they might originally enjoy their sport and be emotionally invested in it, they eventually become disaffected. Participation can be very stressful," Dr. Hill said.

However, the results showed that those players who admitted being more afraid of making mistakes in front of others (a Performance/Ego mindset) were also much more likely to suffer from burnout versus those players that were driven by their own high standards (a Mastery/Task mindset).

"Perfectionism can be a potent energising force but can also carry significant costs for athletes when things don't go well,” Dr. Hill commented. “Perfectionists are stuck in a self-defeating cycle. They are overly dependent on personal accomplishment as a means of establishing a sense of self-esteem but are always dissatisfied with their efforts. Even success can be problematic because they simply become more demanding until they inevitably experience failure.”

His research appears in the Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology.

A coach can have a significant impact on motivating learning by the type of environment they create, one that rewards players for self-improvement alone or one that rewards improvement compared to others. Last year, French researchers surveyed 309 young, elite handball players about four things, their perception of their coach’s motivational environment, their own perceived competence, their type of learning motivation and any symptoms of burnout.

They concluded that “young talented athletes perceiving an ego-involving climate had a higher risk of experiencing burnout symptoms at the season’s end. In contrast, players perceiving a high task-involving climate had lower burnout scores when the season concluded.”

Once again the coach-athlete relationship becomes critical to development of elite potential and performances. The more training data that can be captured and analyzed, the better the subtle hints of burnout can be detected.