After The Game, Get Off The Couch

/

Spending too much leisure time in front of a TV or computer screen appears to dramatically increase the risk for heart disease and premature death from any cause, perhaps regardless of how much exercise one gets, according to a new study published in the January 18, 2011, issue of the Journal of the American College of Cardiology.

Data show that compared to people who spend less than two hours each day on screen-based entertainment like watching TV, using the computer or playing video games, those who devote more than four hours to these activities are more than twice as likely to have a major cardiac event that involves hospitalization, death or both.

The study -- the first to examine the association between screen time and non-fatal as well as fatal cardiovascular events -- also suggests metabolic factors and inflammation may partly explain the link between prolonged sitting and the risks to heart health.

The present study included 4,512 adults who were respondents of the 2003 Scottish Health Survey, a representative, household-based survey. A total of 325 all-cause deaths and 215 cardiac events occurred during an average of 4.3 years of follow up.

"People who spend excessive amounts of time in front of a screen -- primarily watching TV -- are more likely to die of any cause and suffer heart-related problems," said Emmanuel Stamatakis, PhD, MSc, Department of Epidemiology and Public Health, University College London, United Kingdom. "Our analysis suggests that two or more hours of screen time each day may place someone at greater risk for a cardiac event."

In fact, compared with those spending less than two hours a day on screen-based entertainment, there was a 48% increased risk of all-cause mortality in those spending four or more hours a day and an approximately 125% increase in risk of cardiovascular events in those spending two or more hours a day. These associations were independent of traditional risk factors such as smoking, hypertension, BMI, social class, as well as exercise.

The findings have prompted authors to advocate for public health guidelines that expressly address recreational sitting (defined as during non-work hours), especially as a majority of working age adults spend long periods being inactive while commuting or being slouched over a desk or computer.

"It is all a matter of habit. Many of us have learned to go back home, turn the TV set on and sit down for several hours -- it's convenient and easy to do. But doing so is bad for the heart and our health in general," said Dr. Stamatakis. "And according to what we know so far, these health risks may not be mitigated by exercise, a finding that underscores the urgent need for public health recommendations to include guidelines for limiting recreational sitting and other sedentary behaviors, in addition to improving physical activity."

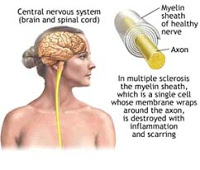

Biological mediators also appear to play a role. Data indicate that one fourth of the association between screen time and cardiovascular events was explained collectively by C-reactive protein (CRP), body mass index, and high-density lipoprotein cholesterol suggesting that inflammation and deregulation of lipids may be one pathway through which prolonged sitting increases the risk for cardiovascular events. CRP, a well-established marker of low-grade inflammation, was approximately two times higher in people spending more than four hours of screen time per day compared to those spending less than two hours a day.

Dr. Stamatakis says the next step will be to try to uncover what prolonged sitting does to the human body in the short- and long-term, whether and how exercise can mitigate these consequences, and how to alter lifestyles to reduce sitting and increase movement and exercise.

Source: American College of Cardiology and Emmanuel Stamatakis, Mark Hamer, and David W. Dunstan. Screen-Based Entertainment Time, All-Cause Mortality, and Cardiovascular Events: Population-Based Study With Ongoing Mortality and Hospital Events Follow-Up. Journal of the American College of Cardiology, 2011; 57: 292-299 DOI: 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.05.065

See also: Exercise - The Cure For The Common Cold and Training In The Heat Even Helps Competing In Cool Temps

Data show that compared to people who spend less than two hours each day on screen-based entertainment like watching TV, using the computer or playing video games, those who devote more than four hours to these activities are more than twice as likely to have a major cardiac event that involves hospitalization, death or both.

The study -- the first to examine the association between screen time and non-fatal as well as fatal cardiovascular events -- also suggests metabolic factors and inflammation may partly explain the link between prolonged sitting and the risks to heart health.

The present study included 4,512 adults who were respondents of the 2003 Scottish Health Survey, a representative, household-based survey. A total of 325 all-cause deaths and 215 cardiac events occurred during an average of 4.3 years of follow up.

"People who spend excessive amounts of time in front of a screen -- primarily watching TV -- are more likely to die of any cause and suffer heart-related problems," said Emmanuel Stamatakis, PhD, MSc, Department of Epidemiology and Public Health, University College London, United Kingdom. "Our analysis suggests that two or more hours of screen time each day may place someone at greater risk for a cardiac event."

In fact, compared with those spending less than two hours a day on screen-based entertainment, there was a 48% increased risk of all-cause mortality in those spending four or more hours a day and an approximately 125% increase in risk of cardiovascular events in those spending two or more hours a day. These associations were independent of traditional risk factors such as smoking, hypertension, BMI, social class, as well as exercise.

The findings have prompted authors to advocate for public health guidelines that expressly address recreational sitting (defined as during non-work hours), especially as a majority of working age adults spend long periods being inactive while commuting or being slouched over a desk or computer.

"It is all a matter of habit. Many of us have learned to go back home, turn the TV set on and sit down for several hours -- it's convenient and easy to do. But doing so is bad for the heart and our health in general," said Dr. Stamatakis. "And according to what we know so far, these health risks may not be mitigated by exercise, a finding that underscores the urgent need for public health recommendations to include guidelines for limiting recreational sitting and other sedentary behaviors, in addition to improving physical activity."

Biological mediators also appear to play a role. Data indicate that one fourth of the association between screen time and cardiovascular events was explained collectively by C-reactive protein (CRP), body mass index, and high-density lipoprotein cholesterol suggesting that inflammation and deregulation of lipids may be one pathway through which prolonged sitting increases the risk for cardiovascular events. CRP, a well-established marker of low-grade inflammation, was approximately two times higher in people spending more than four hours of screen time per day compared to those spending less than two hours a day.

Dr. Stamatakis says the next step will be to try to uncover what prolonged sitting does to the human body in the short- and long-term, whether and how exercise can mitigate these consequences, and how to alter lifestyles to reduce sitting and increase movement and exercise.

Source: American College of Cardiology and Emmanuel Stamatakis, Mark Hamer, and David W. Dunstan. Screen-Based Entertainment Time, All-Cause Mortality, and Cardiovascular Events: Population-Based Study With Ongoing Mortality and Hospital Events Follow-Up. Journal of the American College of Cardiology, 2011; 57: 292-299 DOI: 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.05.065

See also: Exercise - The Cure For The Common Cold and Training In The Heat Even Helps Competing In Cool Temps