Virtual Reality Lab Proves How Fly Balls Are Caught

/

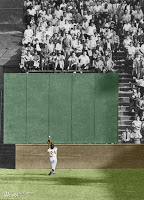

While baseball fans still rank "The Catch" by Willie Mays in the 1954 World Series as one of the greatest baseball moments of all times, scientists see the feat as more of a puzzle: How does an outfielder get to the right place at the right time to catch a fly ball?

Thousands of fans (and hundreds of thousands of YouTube viewers) saw Mays turn his back on a fly ball, race to the center field fence and catch the ball over his shoulder, seemingly a precise prediction of a fly ball's path that led his team to victory. According to a recent article in the Journal of Vision ("Catching Flyballs in Virtual Reality: A Critical Test of the Outfielder Problem"), the "outfielder problem" represents the definitive question of visual-motor control. How does the brain use visual information to guide action?

To test three theories that might explain an outfielder's ability to catch a fly ball, researcher Philip Fink, PhD, from Massey University in New Zealand and Patrick Foo, PhD, from the University of North Carolina at Ashville programmed Brown University's virtual reality lab, the VENLab, to produce realistic balls and simulate catches. The team then lobbed virtual fly balls to a dozen experienced ball players.

"The three existing theories all predict the same thing: successful catches with very similar behavior," said Brown researcher William Warren, PhD. "We realized that we could pull them apart by using virtual reality to create physically impossible fly ball trajectories."

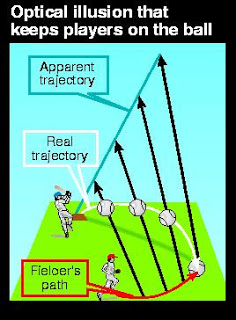

Warren said their results support the idea that the ball players do not necessarily predict a ball's landing point based on the first part of its flight, a theory described as trajectory prediction. "Rather than predicting the landing point, the fielder might continuously track the visual motion of the ball, letting it lead him to the right place at the right time," Warren said.

Because the researchers were able to use the virtual reality lab to perturb the balls' vertical motion in ways that would not happen in reality, they were able to isolate different characteristics of each theory. The subjects tended to adjust their forward-backward movements depending on the perceived elevation angle of the incoming ball, and separately move from side to side to keep the ball at a constant bearing, consistent with the theory of optical acceleration cancellation (OAC). The third theory, linear optical trajectory (LOT), predicted that the outfielder will run in a direction that makes the visual image of the ball appear to travel in a straight line, adjusting both forward-backward and side-to-side movements together.

Fink said these results focus on the visual information a ball player receives, and that future studies could bring in other variables, such as the effect of the batter's movements or sound.

"As a first step we chose to concentrate on what seemed likely to be the most important factor," Fink said. "Fielders might also use information such as the batter's swing or the sound of the bat hitting the ball to help guide their movements."

Sources: Catching fly balls in virtual reality: A critical test of the outfielder problem and Association for Research in Vision and Ophthalmology

Thousands of fans (and hundreds of thousands of YouTube viewers) saw Mays turn his back on a fly ball, race to the center field fence and catch the ball over his shoulder, seemingly a precise prediction of a fly ball's path that led his team to victory. According to a recent article in the Journal of Vision ("Catching Flyballs in Virtual Reality: A Critical Test of the Outfielder Problem"), the "outfielder problem" represents the definitive question of visual-motor control. How does the brain use visual information to guide action?

To test three theories that might explain an outfielder's ability to catch a fly ball, researcher Philip Fink, PhD, from Massey University in New Zealand and Patrick Foo, PhD, from the University of North Carolina at Ashville programmed Brown University's virtual reality lab, the VENLab, to produce realistic balls and simulate catches. The team then lobbed virtual fly balls to a dozen experienced ball players.

"The three existing theories all predict the same thing: successful catches with very similar behavior," said Brown researcher William Warren, PhD. "We realized that we could pull them apart by using virtual reality to create physically impossible fly ball trajectories."

Warren said their results support the idea that the ball players do not necessarily predict a ball's landing point based on the first part of its flight, a theory described as trajectory prediction. "Rather than predicting the landing point, the fielder might continuously track the visual motion of the ball, letting it lead him to the right place at the right time," Warren said.

Fink said these results focus on the visual information a ball player receives, and that future studies could bring in other variables, such as the effect of the batter's movements or sound.

"As a first step we chose to concentrate on what seemed likely to be the most important factor," Fink said. "Fielders might also use information such as the batter's swing or the sound of the bat hitting the ball to help guide their movements."

Sources: Catching fly balls in virtual reality: A critical test of the outfielder problem and Association for Research in Vision and Ophthalmology